Pozhyly/we lived (2022) is a documentary-artistic archive capturing everyday life in Lviv during the first months of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In those days, the city became a temporary refuge, a maze of improvised logistics and daily survival. People poured in from all parts of the country, searching for safety. They slept on couches, floors, in kitchens — wherever there was space — with friends, acquaintances, and strangers.

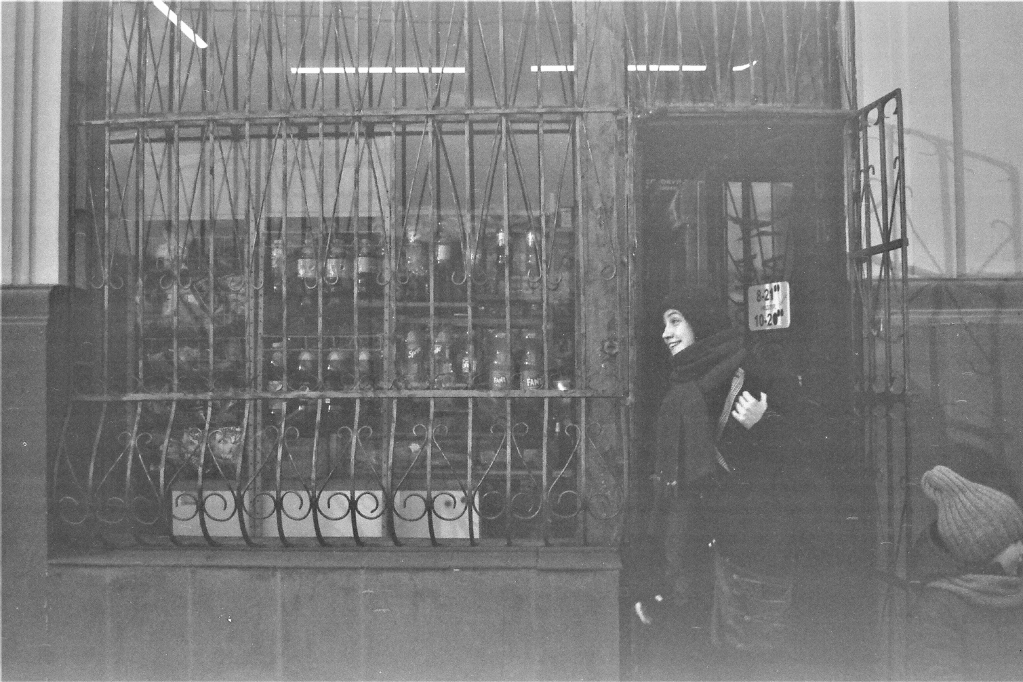

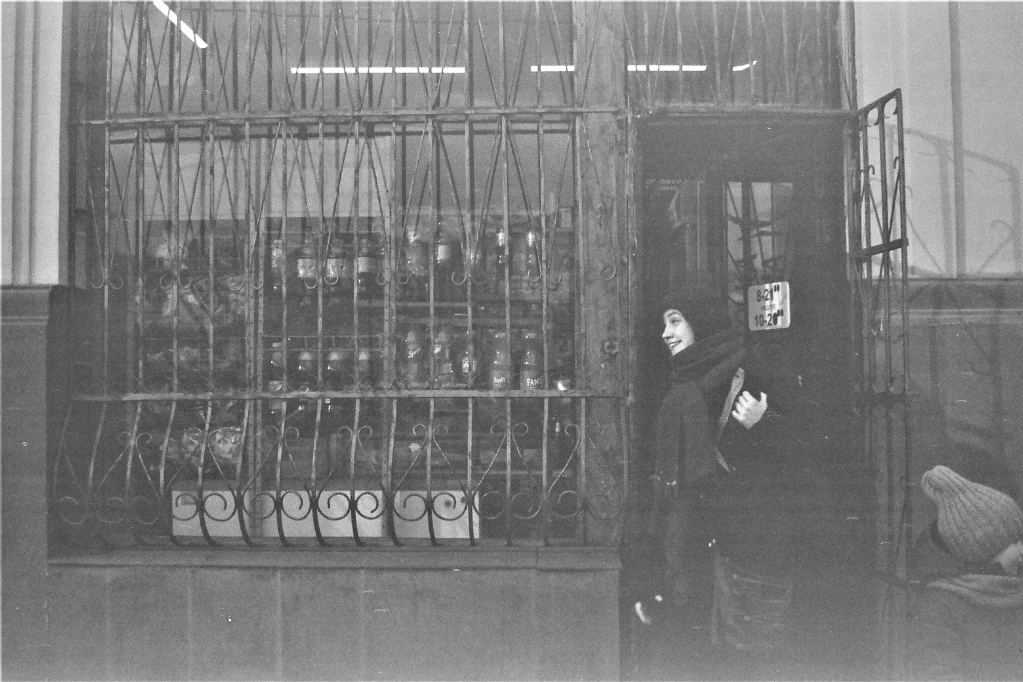

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

The project documents the experience of collective survival and the radical transformation of everyday ethics and routines under a state of emergency. In the atmosphere of constant tension, the boundaries between the personal and the public began to blur, giving rise to a peculiar sense of closeness — born out of fear, necessity, and sudden physical proximity.

Photographs by Kateryna Turenko and Anna Nykytiuk capture this “temporary present” — bodies, routines, gestures, the fear of disappearance, the will to survive, the desire to live.

The project was partly shown in apartment exhibitions and was later presented at the NICHTLEMBERG exhibition in Frankfurt in September 2024.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

The NICHTLEMBERG exhibition examines the “non-Lviv” component of the city’s life during the full-scale war, as well as examples of artistic reflection on past ruptures (ruptures with the past). “Non-Lviv Lviv” here is simultaneously a place of mourning loss and a place where something new is born.

This exhibition aims to initiate a dialogue between Frankfurt and Lviv through the eyes of non-Galician parts of Ukraine. NICHTLEMBERG is organized in cooperation with independent artists and curators from Ukraine and supported by #Kulturamt Frankfurt am Main and private donors of Perspektive Ukraine e.V.

Artists: Elena Subach, Viacheslav Poliakov, Kateryna Turenko, Anna Nykytiuk, Olia Yeriemieieva, Vlodko Kostyrko, Vasyl (Tkachenko) Lyakh, Yaroslav Futymskyi, Oleg Perkowsky, Vlada Ralko, Dasha Chechushkova, Illia Todurkin, Denys Pankratov, Dana Kavelina.

Co-curators: Anna Nykytiuk, Kateryna Turenko, Nikita Kadan.

Curatorial text by Kateryna Turenko. Pozhyly/we lived (2022)

With the start of Russia’s full-scale aggression, Lviv became cramped, like an old house where walls had shifted and rooms got mixed up. Everything blended—time, space, faces. Lviv entirely transformed into a vast temporary shelter, an improvised sleeping place for one night or several months. People sought help through friends and communities—housing strangers and living together until it became impossible. They lived wherever space allowed—in rooms, corridors, kitchens.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

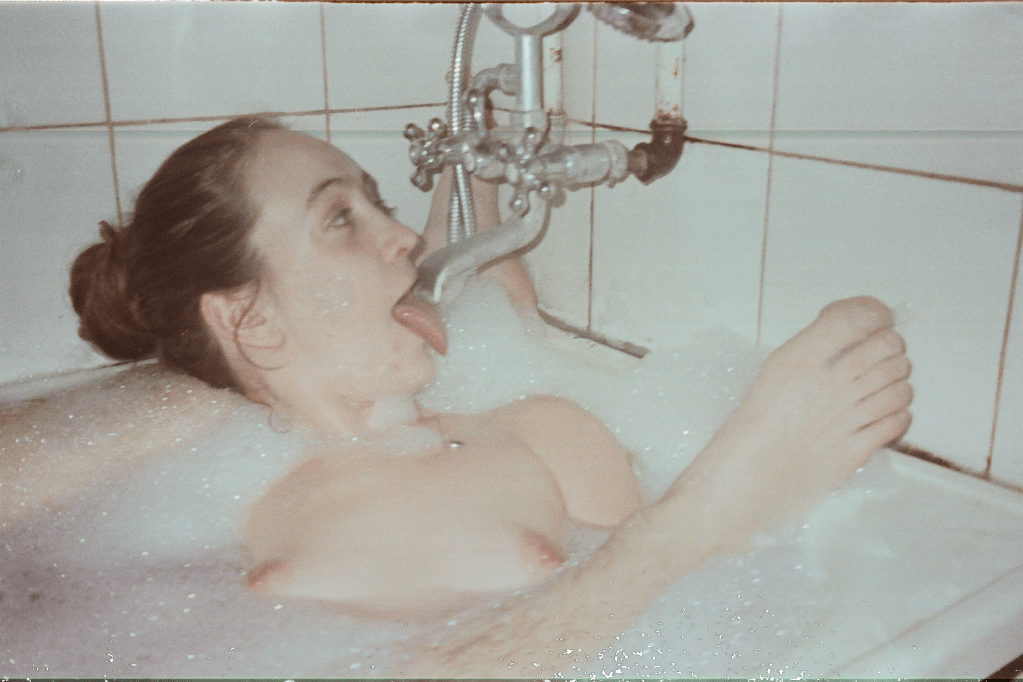

Beyond friends’ and relatives’ apartments, rent prices skyrocketed shamelessly, and often those who couldn’t find affordable housing had to return to less safe cities. In Anya Nykytyuk and Hlib Yashchenko’s two rooms, up to eight people lived: in one, Anya, Hlib, me, sometimes Sasha Kupchenko; in the other, four refugees from Chernihiv, young guys we didn’t know personally before. Anya procured pillows and blankets for everyone from humanitarian aid distribution points. The lack of personal space made daily life less demanding. We slept on mattresses, ate canned food from German humanitarian aid, walked around naked, and pondered how to live on. It was a spontaneous family, and there were many like it. Some artists and activists from Odesa’s squatted shipyard moved to Lviv’s REMA factory, where workshops for life and art proliferated with renewed vigor. At various times, Dasha Chechushkova, Illia Todurkin, Artur Snitkus, Anya Nykytyuk, and Dana Kavelina worked or lived there. While historical heritage was being evacuated from Lviv, refugees brought new art and new stories to the city.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

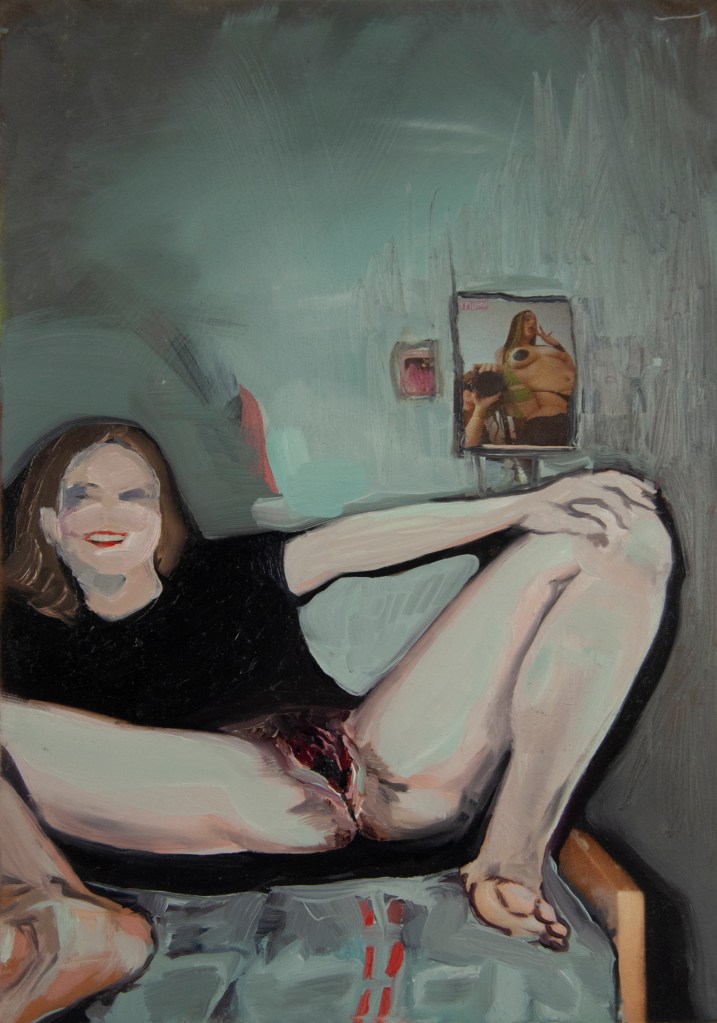

The state of emergency nullified legal and moral norms—there was no tomorrow, and there’s no energy left for shame. It seemed everything was allowed and possible. We drafted rough life programs, outlined spaces for new concepts, for any life we’d dare to imagine and create. And this imaginary expansion of existence’s boundaries was pleasurable. Lviv’s liveliness resembled collective excitement anticipating a big explosion. Pleasure is guaranteed only under the condition of oblivion—and we developed the ability to forget and remember at the right times.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

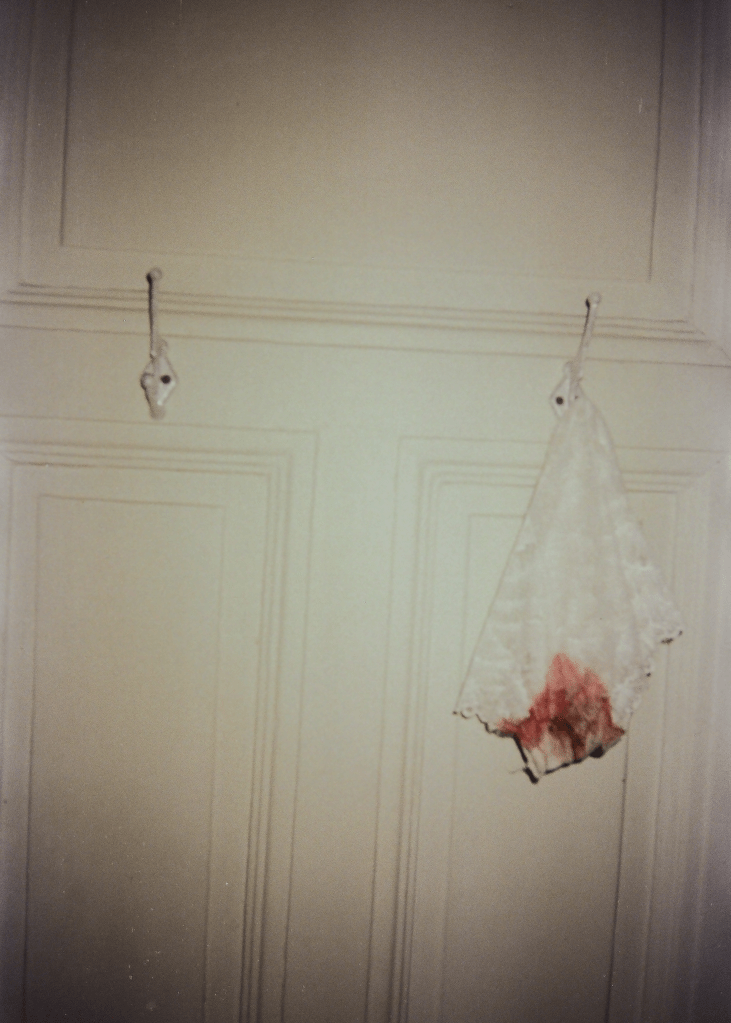

The past was inexorably being materially destroyed or threatened with destruction. We shot a lot on film, wanting to capture the moving present, what was still possible to capture. And it was only possible at home—in the first months after the invasion, photographing on the streets without special permission was suspicious.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

The curfew in March lasted from ten in the evening until five in the morning. Night transformed from a romantic time into stolen time, no longer belonging to us—filled with anxiety and flying missiles. Oleg Perkovsky counts the number of such nights in his work. Simultaneously, the usual etiquette shifted—one could always stay where they had lingered as guests.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

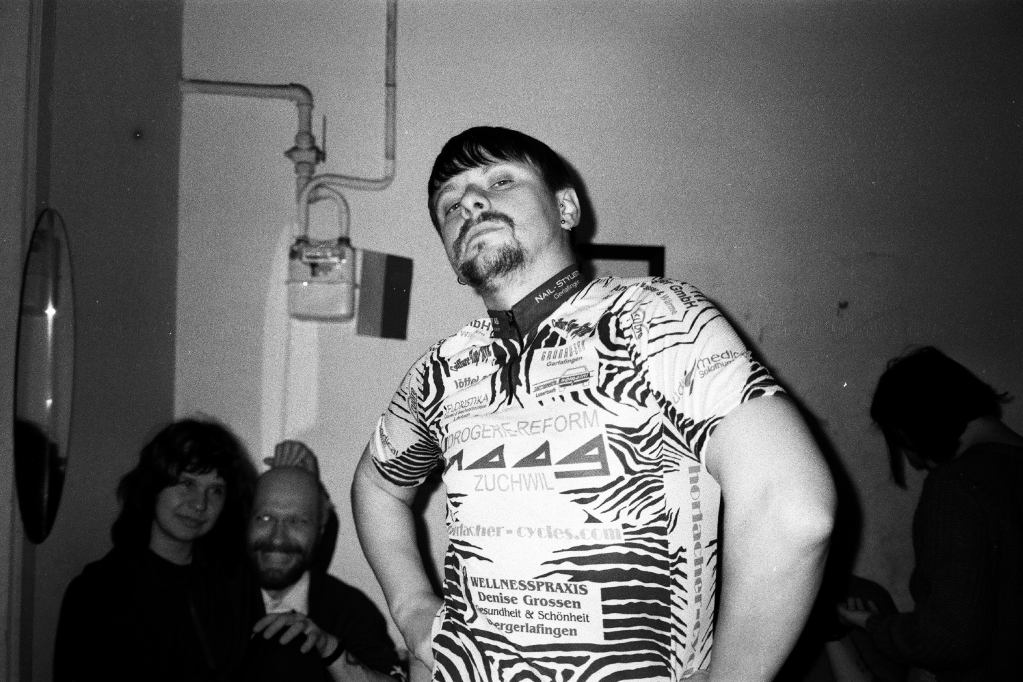

We observed each other. The camera passed from hand to hand, as if it were a separate organ, grown to capture our togetherness and farewell—with each other, with time itself. We knew that tomorrow might not leave us a chance to be together. Olia Yeremieieva mentioned that the body in war becomes the main target of destruction, the goal of terror, that war on many levels is synonymous with torture of the body. In her photos, Artur Snitkus playfully poses in a transparent bodysuit and covers himself with my robe.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

At the end of the evening, we had a terrible argument. We saw him a year later at the REMA factory when Dana Kavelina was filming “Lemberg Machine” there. And this summer, he died at the front. The war took away our chance to meet, remember this, or argue once more.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

Unlike text, Roland Barthes believed, photography is incapable of reflection, but instead provides material for ethnological knowledge—a collection of partial objects. What got into the frame, and what remained outside it. The “We Lived” archive reminds me that we existed and resisted, made dark jokes and shamelessly rejoiced.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Anna Nykytiuk

On a large invisible X-ray of Lviv, time has layered one upon another—we all sit at one kitchen table, simultaneously and together.

Curatorial text by Nikita Kadan. THE NICHTLEMBERG exhibition in Frankfurt in September 2024

NOTLVIV

Lemberg, Lwów, Львів — names of the city in the 20th century. The exhibition’s title is situationally adjusted to enhance the discomfort of its perception by the local audience depending on the location of the show.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

In the first days of the full-scale war, people streamed to Lviv; from Odesa and Lysychansk, Mariupol and Kyiv, Kharkiv and Chernihiv. This way, the crowd on Lviv’s streets changed. The demand in the rental housing market changed. The artistic life changed.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

In Lviv’s rich artistic history, the time when the city filled with refugees from the Russian invasion has already become a fixed epoch, a chapter in a textbook, a period marked by a milestone. During this time, the city’s cultural landscape became incredibly diverse. As often happens in periods of historical upheaval, this diversity was rootless, unstable, and marked by a mix of boldness and uncertainty. The absence of a more or less clear vision of the future led to the maximum intensity of the present. A feast during cholera, an orgy, a potlatch. The art of “internally displaced” artists is the art of today as the art of the last day. It knows nothing of tomorrow and doesn’t particularly dwell on questions of connection with the past.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

However, as of now, many of the temporary residents of Lviv from 2022-23 have either moved across the western border or returned to places that danger has (mostly) bypassed — primarily to Kyiv. The epoch of “culture of the internally displaced” has not ended, but its Lviv component is currently fading. Which, however, does not mean that it will not intensify again, under circumstances of a new level of catastrophism.

NOTLVIV is an exhibition about the impact of war realities on artistic life through factors of danger and migration. At the same time, it’s an exhibition about the sensory aspects of living through a catastrophe. On how the prospect of total annihilation contributes to exposure.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

But our exhibition has another aspect, a historical one. In central-eastern Ukraine, the exemplarily “western” Lviv is typically perceived as a city of deep tradition, extraordinary historical rootedness, centuries-old continuity. This respectful stereotype is extremely far from reality. Lviv, which survived the break with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and at the same time with “Central Europe” in favor of “Eastern” after World War I, lost its Jewish component during World War II, and the Polish one immediately after. Now the erasure of the Soviet cultural layer is taking place. And every time after the old dies or is displaced, the new gets a chance. Each destruction was followed by a passionate rise. The former involuntarily made space for newcomers — and the latter experienced a small renaissance.

The “non-Lviv” culture filled the recurrently wearied, drained Lviv — and became dominant and actually “Lvivian”. Of course, only in the period between repetitions of the same scenario.

Lviv, 2022. Courtesy: Kateryna Turenko

The exhibition NOTLVIV examines the period of renewal of the city’s art scene during the full-scale Russian invasion and the wave of internal displacement, but examines it in the context of Lviv’s recent history as a history of ruptures, those catastrophes that were followed by an impulse to return to life. Lviv’s historical rebirths are its repeated transformations into “Not-Lviv”. Lemberg, Lwów, Львів — these are figures of loss and recovery. They consistently leave the historical scene to give place to the new — but also to return in a rejuvenated form through the forces of this new.